Being under the weather is never a pleasant experience, but one advantage, if it can be called that, is that it magically puts extra time on one’s hands which was never there before. So, when I found myself housebound in that predicament last week, I decided to give the old school way of reading a shot to see what it felt like. For the last fifteen years or so, almost all my reading has been confined to the digital mode which, with its scalable fonts, obviates the need for reading glasses, its greatest advantage, in addition to, of course, accessibility and portability.

When I looked over my thinned-out bookshelf, my eyes fell on 84, Charing Cross Road, a slim enough volume that I had first read decades ago in the mid-70s. The book is a collection of letters between the author, Helene Hanff, a television scriptwriter based in New York, and Frank Doel, the manager of an “antiquarian” bookshop, Marks & Co., and his staff in London.

When I looked over my thinned-out bookshelf, my eyes fell on 84, Charing Cross Road, a slim enough volume that I had first read decades ago in the mid-70s. The book is a collection of letters between the author, Helene Hanff, a television scriptwriter based in New York, and Frank Doel, the manager of an “antiquarian” bookshop, Marks & Co., and his staff in London.

The book had touched my heart the first time I read it, as much for its utter simplicity as the author’s love for books and her references to the gems of English literature that I had read a few years earlier while studying for my masters in English literature. No wonder then that I admired the author’s request-list of books: Lamb’s Essays of Elia, Donne’s Sermons (although I liked his metaphysical poetry more), Hazlitt’s Essays, Quiller-Couch’s The Oxford Book of English Verse, Pepys’ Diary, Walton’s The Compleat Angler and the Life of Donne … the list goes on.

Helene, for various reasons, kept putting off her visit to London. She never got to meet Frank, who suddenly died of peritonitis in 1968. When I first read this book, this was a sad enough event, but now, decades later, the understated pathos of it hit me particularly hard, most likely a reminder to self not to put off meeting old friends or traveling to once-familiar distant haunts. The book had not changed; but the reader most definitely had, with all the experiences of four decades.

Also, in the process, a mystery of the same vintage was solved. Those were the days before the Internet, and if I had to look up an extra-difficult word that was not in the Oxford Dictionary at home, or a piece of information not in the Reader’s Digest Encyclopedia, I had to dress up and walk about two miles in sweaty heat or muddy rain (those were the only two options) to the town library to hunt through dusty tomes for the answer, which nearly half the time was elusive even at the public library.

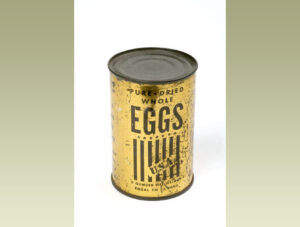

What mystified me then was Helene sending eggs from New York to London, along with other items of food. I knew, of course, that there was rationing in England during the war, but I could not figure out how the eggs made it safely across the pond without getting smashed or spoilt in transit. (As an aside, from the dates of the letters I am amazed at the speed of mail in those days, and that too during the war. It seems to me, overseas mail takes longer in our time, even without the pandemic.) The eggs remained an unsolved riddle for four decades till the second reading of the book. With Google at one’s fingertips, literally, a few taps on my cellphone were all it took to discover the secret—dried egg powder in tin cans shipped from the US to England to overcome the wartime shortage of eggs there, not eggs in their shells. A tin contained the equivalent of twelve eggs and was the ration for four weeks, at three eggs a week, I learned.

What mystified me then was Helene sending eggs from New York to London, along with other items of food. I knew, of course, that there was rationing in England during the war, but I could not figure out how the eggs made it safely across the pond without getting smashed or spoilt in transit. (As an aside, from the dates of the letters I am amazed at the speed of mail in those days, and that too during the war. It seems to me, overseas mail takes longer in our time, even without the pandemic.) The eggs remained an unsolved riddle for four decades till the second reading of the book. With Google at one’s fingertips, literally, a few taps on my cellphone were all it took to discover the secret—dried egg powder in tin cans shipped from the US to England to overcome the wartime shortage of eggs there, not eggs in their shells. A tin contained the equivalent of twelve eggs and was the ration for four weeks, at three eggs a week, I learned.

[By unknown, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22140554]

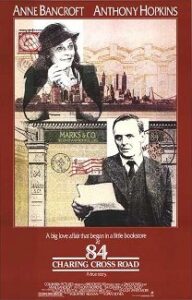

I cannot for the life of me imagine how this book of letters between a bibliophile and the manager and staff of a bookshop could have been turned into a movie. But that it has been, and a well-received one at that, starring Anne Bancroft, Anthony Hopkins, and Judi Dench, directed by David Jones, and produced by Mel Brooks (no less!), Anne Bancroft’s husband.

Must stream that movie from my cellphone to the television one of these days and not wait for the next ailment to show up uninvited to free up time.