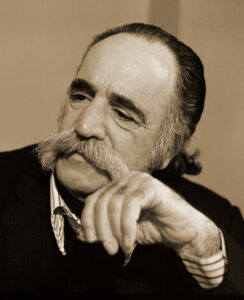

While at university I had stumbled upon William Saroyan, the Armenian-American author, and immediately fell in love with his style of writing from the heart. Saroyan’s values resonated with my ideals during those formative years.

“I do not believe in races. I do not believe in governments. I see life as one life at one time, so many millions simultaneously all over the earth. Babies who have not yet been taught to speak any language are the only race of the earth, the race of man: all the rest is pretence, what we call civilization, hatred, fear, desire for strength.”

This quote from ‘Seventy Thousand Assyrians’ struck a chord in my heart then and has stayed with me all these years. That is what I believe even today without any caveats whatsoever.

This quote from ‘Seventy Thousand Assyrians’ struck a chord in my heart then and has stayed with me all these years. That is what I believe even today without any caveats whatsoever.

In the same story, there is the following paragraph as well.

“Years ago, when I was seventeen, I pruned vines in my uncle’s vineyard, north of Sanger, in the San Joaquin Valley, and there were several Japanese working with me, Yoshio Enomoto, Hideo Suzuki, Katsumi Sujimoto, and one or two others. These Japanese taught me a few simple phrases, hello, how are you, fine day, isn’t it, good-bye, and so on. I said in Japanese to the barber student, “How are you?” He said in Japanese, “Very well, thank you.” Then, in impeccable English, “Do you speak Japanese? Have you lived in Japan?” I said, “Unfortunately, no. I am able to speak only one or two words …”

When I obtained my amateur radio license two decades after university, the above paragraph of Saroyan took on a new, more personal meaning. After developing a close affinity to Japanese amateur radio operators for their politeness, helping attitude, and orderliness, I endeavored to learn a few words of Japanese to help with on-the-air conversations. My efforts yielded ample fruit and helped establish a closer rapport with Japanese hams than would have otherwise been possible.

But it was another two decades later when work took me to Armenia that William Saroyan came fully alive for me. I discovered that everything that Saroyan wrote about the Armenian people were true. That visit was a lifechanging experience and I have made the pilgrimage to Armenia every year since then, except for the Covid years.

But I digress. In the story ‘Seventy Thousand Assyrians’ Saroyan goes for a haircut and asks Theodore Badal the barber if he was Armenian. Saroyan’s reason for the query:

reason for the query:

“We are a small people and whenever one of us meets another, it is an event. We are always looking around for someone to talk to in our language.”

Alas, Badal was an Assyrian – not an Armenian. Yet, during the “fifteen-cent haircut” Saroyan did his “best to learn something at the same time, to acquire some new truth, some new appreciation of the wonder of life, the dignity of man.”

Badal laments the destruction of Assyria and Saroyan grieves about the tragedies that befell Armenia. (Saroyan’s story, written in 1934, does not contain the term ‘genocide’ which was coined ten years later in 1944.)

In spite of his intense sorrow, Saroyan does not harbor any hate or malice towards the perpetrators of the Armenian tragedy.

“I think now that I have affection for all people, even for the enemies of Armenia, whom I have so tactfully not named. Everyone knows who they are. I have nothing against any of them because I think of them as one man living one life at a time, and I know, I am positive, that one man at a time is incapable of the monstrosities performed by mobs. My objection is to mobs only.”

But I digress. What is the connection with a haircut? In the story Saroyan goes no to write:

“I hadn’t had a haircut in forty days and forty nights, and I was beginning to look like several violinists out of work. You know the look: genius gone to pot, and ready to join the Communist Party.”

Saroyan instructs Badal, the barber, of Assyrian origins:

“Leave it full in the back. I have a narrow head and if you do not leave it full in the back, I will go out of this place looking like a horse. Take as much as you like off the top. No lotion, no water, comb it dry.”

Being skinny and gangly in my youth, I had faced the same problem. A haircut at the hands of a crude, uncaring barber made me look more like a steed than anything else. From the time I read this story of Saroyan I never entered a barbershop again and preferred to trim the hair by myself once every two weeks. The only two exceptions being once in the early ‘80s in Stockholm, which was unavoidable, and today entirely due to lethargy.

Today, at the barbershop in Shillong in the Khasi Hills in the North-East of India, where I am presently, I paraphrased Saroyan as best as I could in Hindi and I think I got through because the barber from Bihar (no Badal!) did a decent enough job for me to emerge, I hope, not looking like a jaded draught horse into a world that is riven with hate, ideological conflict, rampant destruction, and heightened cruelty of man towards man. In short, everything that Saroyan spoke up bravely against.

There’s only so much a haircut can do.